Utility Spells — The Magical Metric in Worldbuilding

Whenever I start up a new game with an expansive world and lore, I’m often hit with the eternal question: what kind of build will I use? Having fewer brain cells than thumbs, I’m often tempted to pick up a big stick and just unga bunga my way through the land. However, it’s not exactly the best way to immerse myself in the setting of the game in question.

For example, my first playthrough of Tainted Grail: Fall of Avalon started with a similar struggle. I really wanted to go with a knight in shining armour to fit the Arthurian vibe, but apparently, the world had quite a bit of story entwined around the mystical forces plaguing the land and its people.

Magic, then, would be the answer.

I’ve always held that the arcane arts are a great litmus test for any bit of media featuring the mystical, as their use tells you quite a bit about the creator. How widespread is magic, what is it used for, and what does it cost are all great factors that can differentiate a setting and give it some depth beyond the occasional fireball.

Looking at Tainted Grail with these new magical goggles, it’s plain to see that it is focused on combat; all of the spells (sans one dairy incantation) are more or less made to serve the caster in combat, be it in creating protection, dealing damage, or summoning aid. We also don’t really see anyone else using the skills outside of violence, with open practitioners, the druids, being shunned or killed.

As such, the main character's ability to find and master complex spells with little to no effort seems to conflict with the world itself, making the system feel separate, tacked on, and without any rules. There is so little magic in the world; why are we able to wield so much of it?

As a counter-example, the Elder Scrolls franchise has some stellar samples of intertwining its Magicka into the worlds it creates. In addition to the combat-focused firebolts and shields, you have spells for opening locked objects, charming people, and even creating your own fungal abode! Even the other people of the world often react to your magical shenanigans, making the mystical powers seem more like a part of the world, not just your toy.

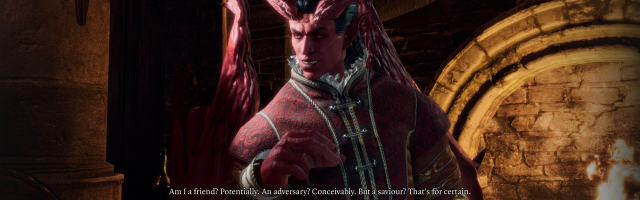

One of the best examples of everyday spells and their use in worldbuilding is Baldur’s Gate 3. Though it may be slightly unfair to give laurels to a game backed by decades of evolution and fine-tuning in the tabletop RPG circles, it is undeniable that the game offers a staggering amount of freedom for a caster to spread their wings.

What I love about the setting and its magic is that it truly feels like something that has evolved in the use of regular people. Sure, we have the basic cones of frost and massive detonations, but we also have an easy spell to conjure little bulbs of light to read with.

I can see the fledgling wizard using a Mage Hand to grab the coffee from the table one room away, or the cleric subtly casting Plant Growth to cover for their poor gardening skills! It’s this utility that makes magic feel real and a part of everyday life, instead of a fancy lightshow that boils down to just doing damage.

Now, before you start waving your wands in protest, I’m not saying we shouldn’t have epic spells that change the flow of battle, nor am I saying magic users should have a spell to do everything better than any expert. As in anything, moderation is key.

A wizard with flowing robes could cast a spell to open a door, but the thief could probably do it in half the time and with much less loud chanting and decades of learning. However, the fact that the magical practitioner could do almost anything also explains the allure of the field and why it is both feared and coveted.

If a writer finds themselves creating a world with mystical energies flowing about and incantations waiting to be spoken, my advice is as follows:

Ask what the greatest practitioner of your form of magic should be able to do, and then ask what the greenest novice could conjure. Once that's done, ask yourself what they would do on their days off, or when they’re feeling lazy. How would they exploit their magical potential, and how would the world around them do the same? You cannot tell me an exhausted mage would not figure out a way to synthesise coffee from the ether.

After the basics of spell-splining tomfoolery are settled, the next topic for introspection is what limits your arcanists should have. Should they be able to show up the royal chef at cooking, or should they be able to do everything well, but not too well? Are there areas where the magical powers have no sway, like baking, which is already some kind of esoteric art in itself, I’m sure.

To summarise my thoughts, a saying used in software development security comes to mind: “baked in, not bolted on”, which is used to signify how security features should be planned at the same time as the features, not added after the fact. In worldbuilding, it is the same! If magic isn’t a part of the world, it will show quite quickly.

COMMENTS